|

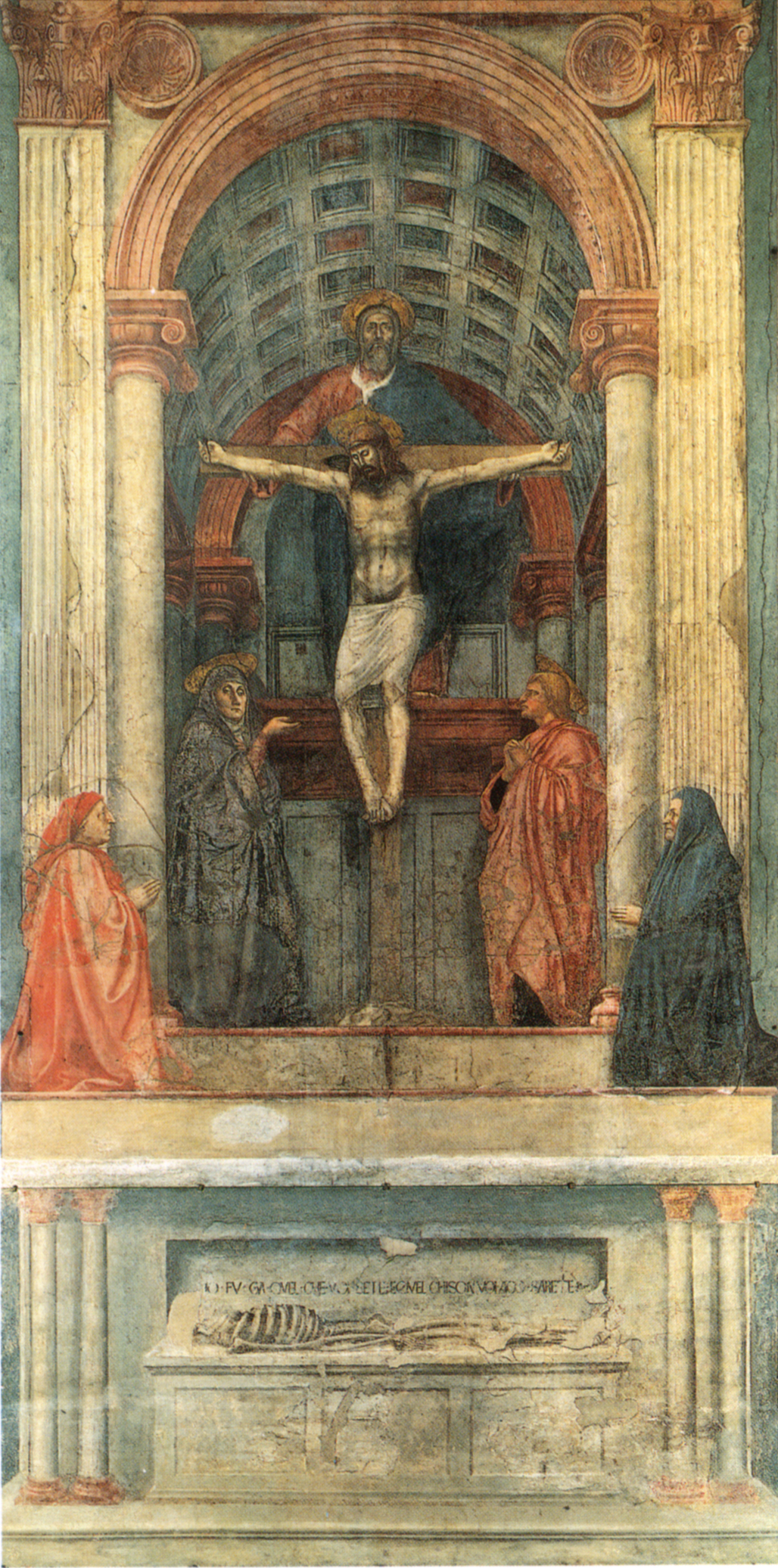

| Masaccio - Holy Trinity |

Reexamining The Perspective Hinge through the lens of animation sheds new light upon the aesthetic of vision, framing, and architecture. It also alleviates some issues that one may have with theories of representation, giving a historical focus to the practice. "For architects concerned with ethics and not merely with aesthetic novelty, who seek the realization of places where a fuller, more compassionate human life might take place, that these mediating artifacts [drawings, models, animations, etc.] and tools be appropriate is paramount." The understanding of vision evolved through the classical and medieval eras, prior to the mathematics and geometries that grew out of the Renaissance. It was in this period that light, spaciality and framing became important. These qualities are visible in the realm of animation, not only in the way one positions the environment but also in the way one designs, particularly with respect to views. Architectural tropes were employed in order to frame the audiences understanding within their built environment. For example, the fenestration in Hagia Sofia hides the massive structure that holds the dome, elevating the religiosity of the space and altering the perception between interior and exterior. In a similar way the camera in an animation program can be controlled in order to reveal or deny view, giving the designer a greater understanding of their space prior to its realization. This realization, however, should pull from the imagination as much as from the software. When drawings become to instructional and the architect is merely a button pusher, the value of the built environment is found sorely wanting. Drawings and the buildings they produce serve a function, but functionality can sway between the beautiful and mundane. It is important to pull from the past when harnessing the medium of the present in order to more intelligently shape the future.